Raccoon Stealer v2 Malware Analysis

Introduction

Raccoon Stealer is an infostealer sold on underground hacker/cybercriminal forums, first observed in early 2019. Raccoon Stealer v2 first appeared in June of 2022, after the developers returned from a supposed “retirement” which they had announced in early 2022. [1] Just as with Raccoon Stealer v1, v2 is capable of stealing information to include cookies and other browser data, credit card data, usernames, and passwords.

Technical Analysis

Raccoon Stealer v2 is written in C/C++, and coming in at only ~57kb, it is fairly lightweight. Below are the hashes for the packed sample, and the unpacked sample. Based on my research, Raccoon Stealer is not sold packed by default, rather, any packing must be done by the customer who will deploy the malware.

- Packed SHA256: 40daa898f98206806ad3ff78f63409d509922e0c482684cf4f180faac8cac273

- Unpacked SHA256: 0123b26df3c79bac0a3fda79072e36c159cfd1824ae3fd4b7f9dea9bda9c7909

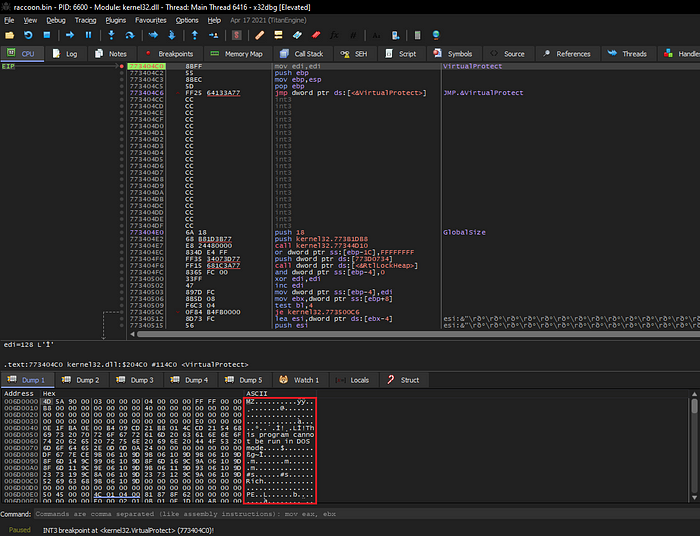

Unpacking

Unpacking this sample is pretty straightforward. All I did was place breakpoints on a few API calls of interest such as VirtualProtect, WriteProcessMemory, CreateProcessInternalW, and VirtualAlloc. Once the VirtualProtect breakpoint is hit, I followed the address in the EAX register in the memory dump, then ran the program again until the next breakpoint. After that, I was able to dump the payload from memory and continue my analysis.

Resolving Imports

To start off, I opened the payload in PEstudio to perform some basic static analysis, which will guide how I carry out the rest of the analysis. Opening the binary in PEstudio, the small number of imported functions (only 8) leads me to believe that the malware probably resolves its imports dynamically.

Disassembling the binary in Ghidra, I found the import resolver function early on in the binary, as expected. This function simply uses the GetProcAddress API function to load the address of the functions it will need. A few of these functions immediately catch my eye, those being the internet related functions highlighted below in figure 3.

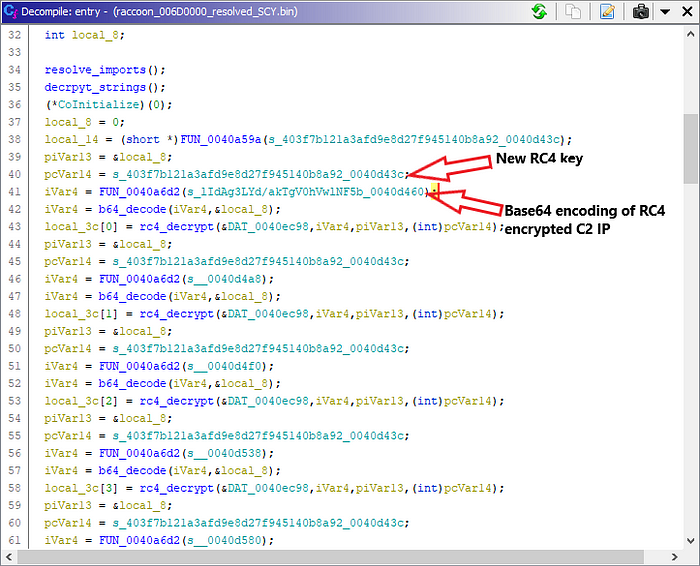

Decrypting Strings and C2 IP Address

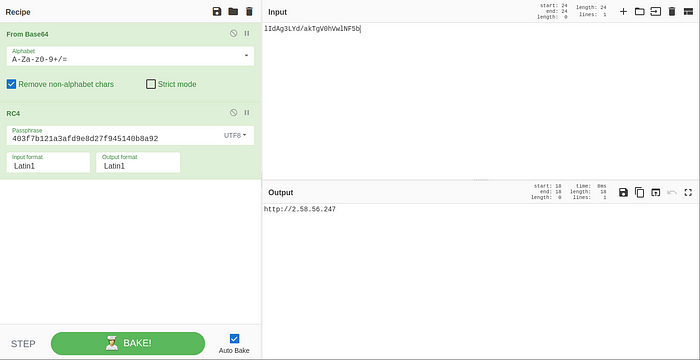

The malware also obfuscates its strings using Base64 encoding and RC4 encryption. The RC4 encrypted strings are stored in the Base64 encoded form. These strings are Base64 decoded, then decrypted using the RC4 key “edinayarossiya”, which means “United Russia” in Russian. Once the strings are decrypted, the malware then performs the same decryption routine for the C2 IP address, but using a different RC4 key.

With this RC4 key and Base64 encoded data, I could use cyberchef to get the IP address of the C2 node.

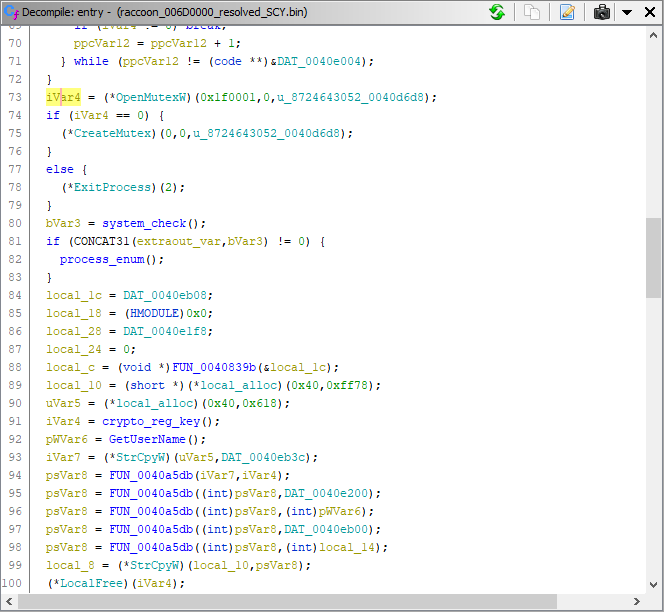

Checking Mutex

Next, the malware checks to see if another instance of it is already running on the infected machine by opening a mutex with the value of 8724643052. If the OpenMutexW function fails and returns a 0, the malware creates a mutex with the value, then continues execution. If the function succeeds and returns 1 (true), the malware exits.

SYSTEM Check and Process Enumeration

The malware also checks if it is running as SYSTEM by comparing the current process’s token to the SYSTEM SID, S-1–5–18.

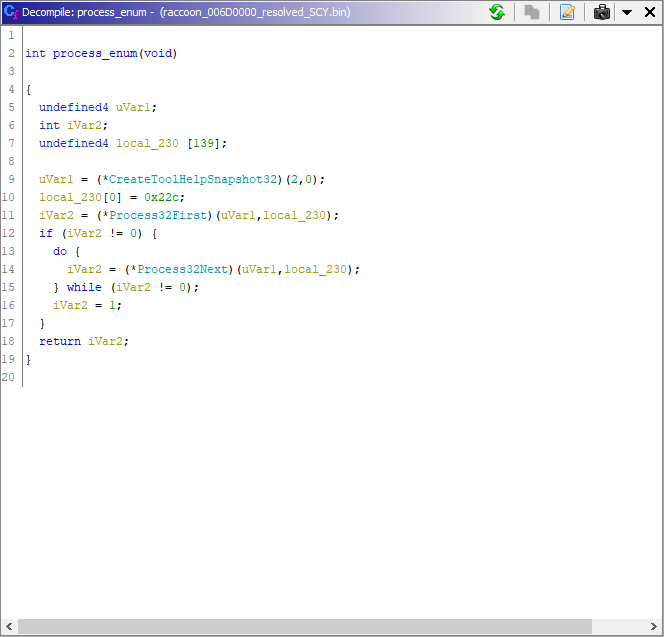

If the malware is running as SYSTEM, it then calls a process enumeration function using CreateToolHelpSnapshot32, Process32First, and Process32Next.

If the malware is not running with SYSTEM privileges, it simply skips over the process enumeration function and continues with its execution.

Host GUID and Username

Before connecting to the C2 node, the malware will retrieve the host’s GUID by querying the SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Cryptography registry key.

The malware also retrieves the current user’s username, and moves it along with the machine ID, onto the heap before contacting the C2 node.

C2 Communication

First the malware uses the WideCharToMultiByte API function to form all of the parameters it needs in order to connect to the C2 node, including the machineID, username, and configID parameters which will be sent to the C2 node via POST request. Of note, the configID parameter is just the RC4 key that was used to decrypt the C2 IP address earlier in the execution.

The malware then checks to see if the response from the C2 node is larger than 0x3f (63 in decimal) characters long. If it is, the malware continues execution. If not, the malware breaks out of the loop and exits.

Unfortunately, at the time I performed my analysis, the C2 IP address did not appear to be up anymore, as Shodan showed that port 3389 (RDP) was the only listening port. Assuming that the C2 node was still operational and able to communicate with the infected host, the C2 node would return several different DLL’s for download to the infected host. Those DLL’s would then be placed in the “C:\Documents and Settings\Administrator\Local Settings\Application Data” folder.

It is at this point that the malware would perform the bulk of its stealing functionality, including cookies, passwords, credit card data, passwords, browser history, etc. [2] Some of this functionality would automatically be executed, and some would require a command from an operator in control of the C2 node.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Raccoon Stealer v2 is a relatively simple, yet very capable info stealer just like v1. Both versions of this stealer pose a threat to organizations of all types, as well as individuals. The information stolen by this malware can be used to take over accounts of all types, financial, social media, corporate, etc.

I hope you enjoyed this post, and that you’ll come back again! A follow and share would be super appreciated. Feedback is certainly welcome as well.

References

[2] https://blog.sekoia.io/raccoon-stealer-v2-part-2-in-depth-analysis/#h-mutex